|

In

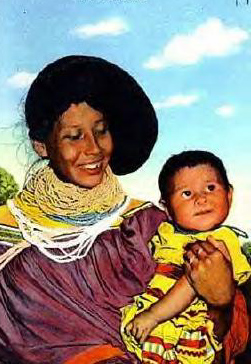

the heart of the Everglades, in a place some call "the middle of nowhere,'" Seminole Indian children

are thriving at a small reservation school. In

the heart of the Everglades, in a place some call "the middle of nowhere,'" Seminole Indian children

are thriving at a small reservation school.

Isolated by an ocean of sawgrass, the school has 142 students _ seven graduates this year _ and a budget that would

make most educators swoon.

And following an intense effort to improve student performance, the Seminole tribe's Ahfachkee School earned a

Title I Distinguished School award, the only Indian-run school to win the honor. Appropriately, the school's name

means "happy'' in the Seminole language.

"Our goal out here is to be known as a Seminole prep school, where the Seminole children are sent to prepare

them to go off to the better colleges in this country,'' said Sharon Byrd-Gaffney, director of school operations.

"We don't just dream of that, we're doing it.''

Money is part of the equation. The school gets about $800,000 a year from the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The tribe,

buoyed by gaming successes at five casinos around the state, has a $1 million annual education budget. Also, a

staff-to-student ratio of eight-to-one makes it nearly impossible for anyone to slip through the cracks.

Three years ago, the story was different. Low test scores and drop outs plagued the school and federal officials

considered taking over. Tribal leaders sought the help of Patrick Gaffney, the principal and superintendent, and

his wife, Byrd-Gaffney.

Since then, proficiency scores in reading, writing and math have soared, attendance is up 21 percent and the dropout

rate has fallen by 18 percent.

"All the elements we need are here,'' Byrd-Gaffney said. "We have the funding, the support of the community

and the brightest and best students in the world.''

Almost all of Ahfachkee's students are Seminole Indians. The gleaming 10-room school, renovated in 1991, has a

cozy library, computers in every classroom and individualized study courses. A Seminole culture class teaches tribal

history and traditional crafts, along with the Miccosukee language, which some say is dying.

"People who understand their own culture are more understanding of other cultures. It improves self esteem

and leads to better learning,'' said Patrick Gaffney, who has worked as an administrator in native American schools

for 18 years.

"We can offer them the best of both worlds: education comparable to a non-Indian, mainstream curriculum, while

at the same time promoting their indigenous culture.''

It was not always this way. Established in the 1940s in a traditional thatched-roof chickee, the

reservation's school once stopped at the fourth grade. Older tribal members recall long bus rides to the nearest

public schools, which are still 40 miles away. It was not always this way. Established in the 1940s in a traditional thatched-roof chickee, the

reservation's school once stopped at the fourth grade. Older tribal members recall long bus rides to the nearest

public schools, which are still 40 miles away.

"At the time, we don't know what time we're getting up, it was 3 in the morning, or 3:30,'' said Mitchell

Cypress, 53, vice chairman of the tribal council. "You know we lived in a chickee, with no water and no plumbing.

It was kind of rough.''

Like many others, Cypress chose to leave the reservation and attend a BIA-funded boarding school in Oklahoma. Mondo

Tiger, 40, who serves on the tribe's Board of Directors, followed his lead.

"It took hard times to get the school the way it is now,'' said Tiger, whose daughter will attend Ahfachkee

next year. "I've seen the tribe grow from a chickee to where it is now, and education is our number one secret

weapon.''

Toward that end, every student is offered the chance to go to college, with tribal grants. High school teacher

Lee Zepeda attended Stetson University on such a scholarship, and went to law school for two years before realizing

he would prefer to teach.

Zepeda is the grandson of Cory Osceola, an active political leader of a group known as the Independent Seminoles,

in Collier County. Now in his fifth year at Ahfachkee, he said coming back to work on the reservation seemed like

the natural thing to do.

"I just want to help make sure everything keeps moving forward,'' said Zepeda. "The tribe, at this point,

is really getting a lot of momentum, with their economic enterprises, and you always want to make your contribution.''

There are 2,400 Seminole Indians in Florida, many living on five federal reservations around the state. Big Cypress

is the largest, and has a population of about 600.

Located at the end of a long, winding road through the "River of Grass,'' Big Cypress is also the only reservation

with a school. Though isolated, the tightly knit community has the atmosphere of a small town

"Everyone knows everyone, everyone suffers or shares in the rewards,'' said Jim Shore, general counsel for

the tribe.

"I think to most people, if they've never been out there, it would almost feel it is the middle of nowhere,''

Shore said. "But to the local people who have been out there forever, compared to the city type of life, I

think they would rather be out there than anywhere else.''

Seminole Tribe of Florida

http://www.seminoletribe.com/

|

In

the heart of the Everglades, in a place some call "the middle of nowhere,'" Seminole Indian children

are thriving at a small reservation school.

In

the heart of the Everglades, in a place some call "the middle of nowhere,'" Seminole Indian children

are thriving at a small reservation school. It was not always this way. Established in the 1940s in a traditional thatched-roof chickee, the

reservation's school once stopped at the fourth grade. Older tribal members recall long bus rides to the nearest

public schools, which are still 40 miles away.

It was not always this way. Established in the 1940s in a traditional thatched-roof chickee, the

reservation's school once stopped at the fourth grade. Older tribal members recall long bus rides to the nearest

public schools, which are still 40 miles away.