|

|

Indian Art-The Real Deal

by Aaron J. Latham,The Arizona Daily Star

Canku Ota is a copyright of Vicki Lockard and Paul Barry.

Indian

art: How to separate real thing from cheap knockoffs

Indian

art: How to separate real thing from cheap knockoffs

So you're enchanted by the intricate patterns of Navajo rugs.

Or you've always dreamed of owning an elaborately carved Hopi kachina.

But you don't know what's authentic, what's a good deal, what's popular this year.

This is a good time to learn.

Area shops are stocked up for spring and summer visitors. Indian arts shows are regular occurrences. And recent

sightings of Indian jewelry in national catalogs and magazines hint that a surge in interest -and possibly in price

- is coming.

Before you buy, though, consider these tips from Mark Bahti, a nationally recognized authority in the field of

traditional and contemporary Indian arts and crafts. Bahti owns Tucson's Bahti Indian Arts, which his father started

in 1952.

Jewelry

The current craze is for color inlays - tiny pieces of turquoise, coral or malachite

formed into shapes or patterns, Bahti said.

Such work was once done mostly by Zuni artists, but Navajos have entered the field, too.

Inlays are made from natural or block materials, Bahti said. Block turquoise sounds quite authentic, but actually

it's plastic that is colored and textured to look like its namesake.

Block often is priced like the real thing, Bahti said. And even if it's not, know that it's not likely to last

for long - it is about as hard as a guitar pick and can suffer a serious gouge from a pin or sharp edge, he said.

Also popular this year are necklaces of silver, stone or shell beads, Bahti said. While some artists make their

own beads, others buy beads and string them. For highest value, the tag or receipt should say "Indian made,"

not "Indian strung."

Kachinas

Several tribes make kachinas, but Hopis use them ceremonially, and experts consider

only Hopi kachinas to be collectible, he said.

Spotting the difference isn't always easy because Hopi kachinas come in a wide range of sizes, styles and colors.

In general, though, Navajo kachinas tend to incorporate fur and feathers, while Hopi kachinas are more likely to

be all wood. Hopi artists started carving feathers years ago to comply with laws restricting the use of game bird

feathers, Bahti said.

Another clue is price. Because of their craftsmanship and rarity, Hopi kachinas rarely cost less than $100, he

said.

Finally, don't be fooled by trappings of authenticity. Some kachinas and pots have machine-stamped signatures made

to look hand-lettered.

Rugs

If you want a rug, make sure you're looking at a Navajo-made rug, not a copy made

in Mexico.

How to tell?

Look at the long edge and push aside a couple of horizontal threads until you can see the vertical fibers on which

the rug was woven. The outermost row of those vertical fibers may have two threads, but every other row should

be a single thread.

Copies often are made on looms that have two threads on the two outermost rows.

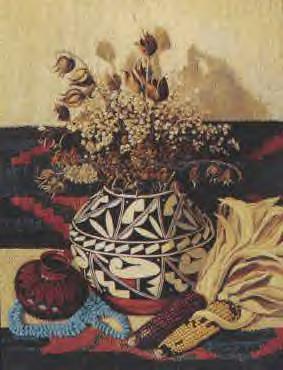

Pottery

Indian pots come in three varieties: hand-formed and hand-painted; greenware, machine-made

pots painted by Indian artists; and pots that are based on Indian designs but are manufactured and painted in overseas

factories.

To spot a factory-made pot, look close: Pots made in molds should have a faint vertical seam.

If you want a handmade and hand-painted pot, make sure the tag or the receipt says "Indian handmade pottery."

Baskets

Baskets, which are made by several tribes, are tough for novices.

Machine-made and Pakistani-made copies are rampant, and unless you know what Indian baskets are made of and what

those materials look like stripped and dried, it's very difficult to spot a fake, Bahti said.

Some manufacturers attach hanging tags with such reassuring language as "authentic" or "handmade,"

Bahti said. What they don't say - because they can't - is that the basket was made by an American Indian.

"Sometimes what they don't say is as important as what they do say," he said.

Fetishes

Fetishes, or tiny animals carved from stone, are often Zuni but also are made by other

tribes.

As with pots, determining authenticity is tough because the art form is changing, Bahti said. In the past, authentic

fetishes tended to be primitive, while fakes were more intricate; not so anymore. In Bahti's display case is a

tiny but lifelike marble grizzly bear carrying an even tinier fish carved from abalone shell.

Knowledge of Indian arts has always been an asset for buyers, Bahti said. But as copies continue to flood the market

- a trend that is likely to increase along with interest - some basic know-how becomes not just helpful but essential,

he said.

"Once the market gets bigger," he said, "it attracts people who are

looking for a fast buck."

Some of those people pass off fakes as authentic, and some willingly admit to selling inexpensive knockoffs. Buying

the cheap stuff may seem to be a good way to take home a little Southwestern flavor, but it can make life tough

for native artisans, Bahti said.

"The buyer is winding up taking food out of the mouths of artisans," he said.

![]()

Canku Ota is a free Newsletter celebrating Native America, its traditions and accomplishments .

We do not provide subscriber or visitor names to anyone. Some articles presented in Canku Ota may contain copyright

material. We have received appropriate permissions for republishing any articles. Material appearing here is distributed

without profit or monetary gain to those who have expressed an interest. This is in accordance with Title 17 U.S.C.

section 107.