|

When a star falls from the sky

It leaves a fiery trail. It does not die.

Its shade goes back to its own place to shine again.

The Indians sometimes find the small stars

where they have fallen in the grass.

A Menominee poem from Gary W. Kronk's "Meteors and the Native Americans"

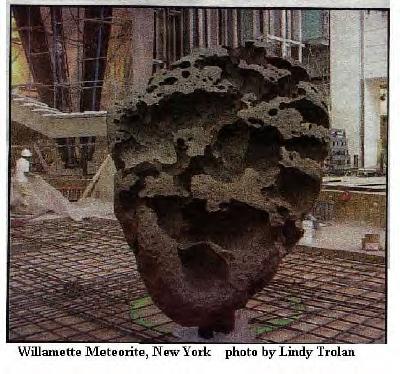

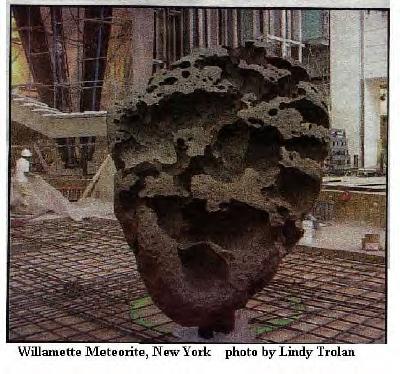

Over the last few years, as the American Museum

of Natural History put up its sleek new planetarium on the Upper West Side, its enormous sphere and glass walls

were erected around one of the museum's oldest treasures, a great 15-ton meteorite that fell to Earth 10,000 years

ago.

For almost

a century, the Willamette Meteorite -- the largest meteor found in the U.S. and believed to have come from the

asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter and brought to the museum from the Pacific Northwest in 1906 -- has been

seen and touched by generations of awed schoolchildren and other fans of the cosmic mysteries.

But as the

$210 million Rose Center for Earth and Space opens at 81st Street near Central Park West to crowds that are expected

to swell to 4.5 million visitors a year, the destiny of the dark, deeply gouged meteorite, seemingly secure on

its steel pedestal in the planetarium's Cullman Hall of the Universe, has been cast into doubt.

Acting under

a federal law written for the preservation and repatriation of Native American cultural and religious artifacts

(NAGPRA), an Indian group in Oregon has submitted a claim for the meteorite, saying it is a holy tribal object

that brought messages from the spirit world long before the arrival of white men.

"This

is a sacred object to the people of the Willamette Valley," Tracy Dugan, speaking for the Confederated Tribes

of the Grand Ronde of Oregon, said. "It was used by our ancestors. We want to bring it back here to our reservation

and make it available for people to use in the traditional way."

The museum

has until Feb. 29 to respond to the claim, which was filed Nov. 30 under the Native American Graves Protection

and Repatriation Act of 1990. The case could wind up in court and take years to resolve, but if no settlement is

reached and the claim is upheld, it would be necessary to partly dismantle the new planetarium to get it out.

Anne Canty,

a spokeswoman for the museum, declined to comment yesterday on the claim for the meteorite. But she acknowledged

that removing it from its new home would be difficult. "Because the meteorite is so massive, parts of the

facility had to essentially be built around it," she said.

The Willamette

Meteorite, a mass of metal and rock the size of a small car, is thought to have plunged down in flames somewhere

in the Pacific Northwest 10 millennia ago, a gnarled monster from space. Shifted by an Ice Age glacier, it came

to rest on a hillside in West Linn, Ore., just south of Portland.

There, the

Clackamas tribe -- one of many groups now part of the Grand Ronde confederation -- took it to be a sacred representation

of sky, earth and water, and adopted it. They called it "Tomanowos," or Sky Person. According to Ms.

Dugan, rain water collected in its craters was considered holy, and Clackamas youths were sent on vigils to the

meteorite to receive messages from the spirit world.

A century

ago, the tribe was confined to a reservation away from the meteorite and its use as a sacred object declined.

In 1902, Ellis G. Hughes, a miner

and farmer, discovered it on land owned by an iron company and had it moved to his barn. He began charging visitors

25 cents to see it. In 1905, the iron company sued for its return and repossessed the meteorite, which had become

a local attraction. In 1902, Ellis G. Hughes, a miner

and farmer, discovered it on land owned by an iron company and had it moved to his barn. He began charging visitors

25 cents to see it. In 1905, the iron company sued for its return and repossessed the meteorite, which had become

a local attraction.

A year later,

a visitor from New York, Mrs. William Dodge, bought the meteorite for $20,600 and donated it to the American Museum

of Natural History. It was moved to New York and became part of the museum's permanent collection. In 1935, when

the Hayden Planetarium opened, it became a centerpiece of its exhibit and over the years was seen and touched by

millions.

Five years

ago, when the museum began work on the Rose Center to replace the

old planetarium, a decision was made to incorporate a few of the old treasures -- including the meteorite and scales

showing what a person would weigh on the Moon and various planets -- into the new building.

The meteorite

was so large and heavy that it had to be installed first, in effect, and the planetarium built around it. Two years

ago, contractors sunk three steel pilings into the ground to support its bulk, and it was swung in on a crane and

mounted in a permanent exhibition hall on the lower level.

Last September,

with the planetarium still under construction, a half-dozen representatives of the Grand Ronde confederation visited

museums in Chicago, Boston and other cities in the East, including the American Museum of Natural History, in search

of cultural and religious artifacts that they might have a right to claim.

The confederation

has a reservation and headquarters in Grand Ronde, Ore., 60 miles southwest of Portland, and 4,500 members in five

main tribes, situated in the Willamette Valley, which stretches south from Portland about 100 miles. The Clackamas

tribe is a subgroup of one of the five main tribes, Ms. Dugan said.

Like many

Native American groups, its chances of recovering lost cultural and religious artifacts seemed hopeless years ago,

especially after many of the smaller tribes were officially "terminated" by the federal government in

1954, under an Eisenhower administration policy aimed at greater assimilation of Indians into American culture.

But after years of lobbying, many of the groups, including the Grand Ronde, were officially resurrected in 1983,

and in 1990 the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act gave new hope to tribes seeking to recover objects,

including bones of ancestors and relics, that had been sacred or culturally important.

Under a federal

grant, the delegation from Grand Ronde -- Ryan and Adrienne Heavy Head, June Olson, Lindy Trolan and others --

visited the Natural History Museum over a period of six days, taking thousands of pictures to

document objects for possible repatriation.

Ms. Dugan said the group was treated civilly, but encountered

resistance from museum officials when they sought to take pictures of the Willamette Meteorite. It was in a hard

hat construction area, they were told. But they were eventually allowed in under supervision and took pictures. Ms. Dugan said the group was treated civilly, but encountered

resistance from museum officials when they sought to take pictures of the Willamette Meteorite. It was in a hard

hat construction area, they were told. But they were eventually allowed in under supervision and took pictures.

Before leaving

the museum, the delegation filed the claim directly with the museum on behalf of the Grand Ronde, Ms. Dugan said.

Documentary evidence to support the claim was filed with the museum on Nov. 30, she said. Under the federal law,

the museum is obliged to respond within 90 days, which she said would elapse on Feb. 29.

Proof of ownership

appears to be the critical issue -- the museum citing its acquisition of and long protective association with the

meteorite, versus the Grand Ronde's claim of ancient tribal religious and cultural ties. The case could go to a

federal review committee or to court, and it could take years to resolve.

Or the two

sides could agree to settle it, although Ms. Dugan suggested that that was doubtful. "So much of Indian culture

has been lost," she said. "Our people were discouraged, even forbidden, to practice their religion. We

want the meteorite back, and not some settlement."

|